Carmen Saeculare: Purpose and Historical Importance. It is easy to misunderstand the Carmen Saeculare if we approach it as we would any other poem by Horace. Read silently on a page, it can appear formal, restrained, even distant. Yet this reaction misses the most important fact about the poem: it was never meant to live on the page. The Carmen Saeculare was written for a single public moment, for a specific audience, and for a purpose that went far beyond literary reputation.

Horace composed the poem for the Secular Games of 17 B.C., a religious festival revived under Augustus to mark the beginning of a new age. Rome had endured years of civil conflict, and the idea of renewal was not abstract. It was political, moral, and deeply symbolic. The poem functioned as part of that symbolism. Its purpose was not to persuade through argument, but to shape feeling—confidence in the present and trust in the future.

The Secular Games and the Idea of a New Roman Age

Understanding this changes how the Carmen Saeculare should be read. It was not a private meditation, nor a philosophical lyric meant for small circles. It was public ceremonial poetry, sung aloud by a chorus of boys and girls before the Roman people. Its meaning unfolded through sound, repetition, and collective presence. In this sense, Latin poetry briefly became a civic ritual rather than a literary object.

The historical importance of the poem lies precisely in this transformation. Under Augustan Rome, poetry stepped into a new role. It became a visible part of state life, without entirely losing its artistic character. The Carmen Saeculare was written for public performance during the Secular Games of 17 B.C., a rare religious festival intended to mark the beginning of a renewed Roman age.

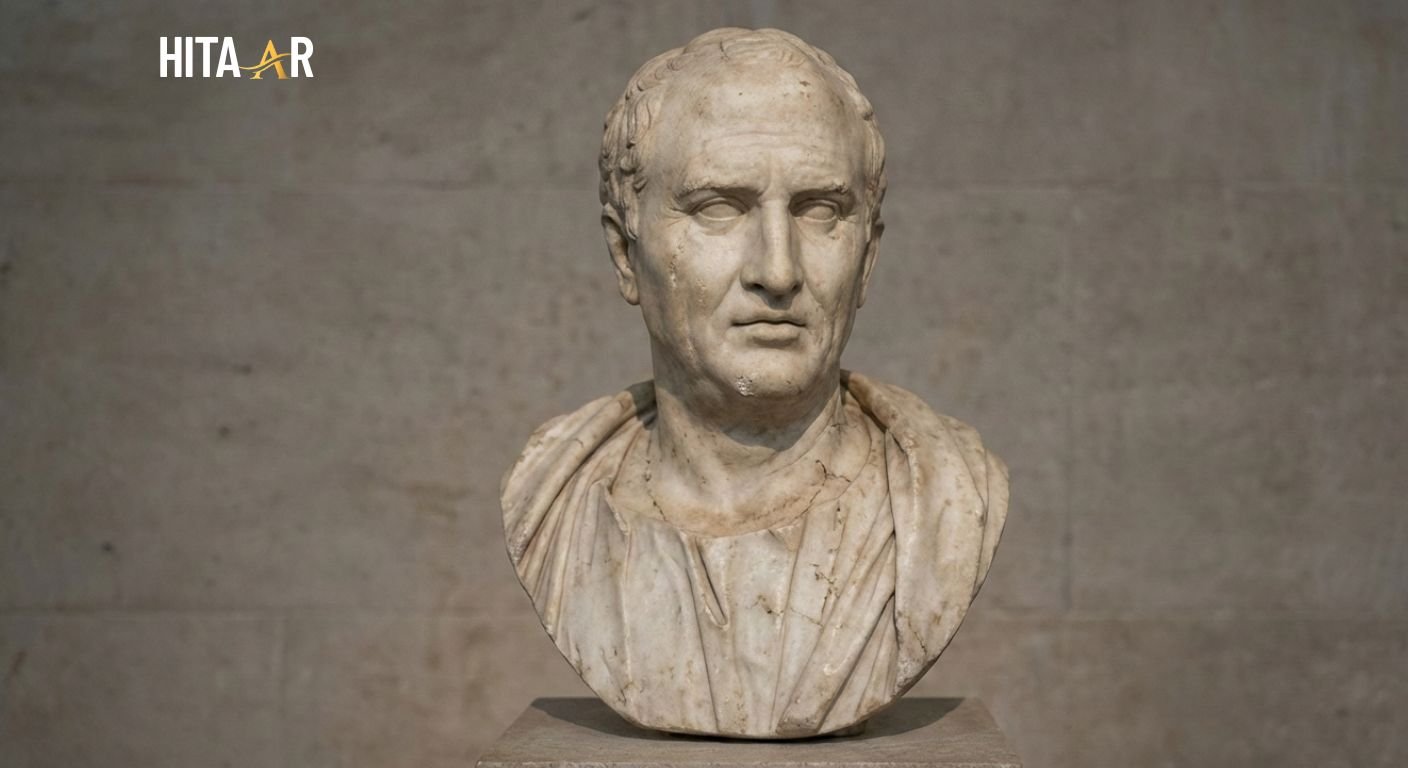

Why Horace Was Chosen to Speak for Rome

Horace was an ideal figure for this task. By this stage in his career, he was already known for his control of Roman lyric poetry and his careful adaptation of Greek forms. He understood restraint, balance, and tone—qualities essential for a poem that would represent Rome itself.

The Carmen Saeculare does not overwhelm its audience with praise. Augustus is not loudly celebrated, nor is Roman power described in heroic language. Instead, the poem focuses on harmony between gods and people, on fertility, peace, and continuity. This choice feels deliberate. Horace seems aware that excess would weaken the poem’s authority. What gives the hymn its weight is not enthusiasm, but calm confidence.

Public Performance and the Power of Shared Voice

The involvement of public performance is central to the poem’s meaning. Sung by a chorus of young voices, the Carmen Saeculare created a shared experience that extended beyond the literary elite. The performers symbolized renewal in a way no speech could. They represented future generations, continuity, and hope.

In that moment, Roman identity was not explained—it was enacted. The poem did not simply describe a new age; it performed it. This performative quality explains why the Carmen Saeculare occupies such a distinctive position within Classical Roman literature.

Restraint, Balance, and Augustan Values

This restraint reflects broader patterns within Augustan literature. The Age of Augustus favored order over display, permanence over drama. The poem’s measured voice aligns with this cultural mood. At the same time, it avoids sounding like a political proclamation.

Horace does not instruct his audience on how to think; he assumes shared values already exist. That assumption itself tells us something important about the Roman audience the poem addressed.

Religion, Renewal, and Moral Order

The involvement of religion further strengthens the poem’s significance. By invoking Apollo and Diana, the Carmen Saeculare connects Rome’s political future to divine favor. Yet the gods are not distant or threatening. They appear as protectors of social balance and moral health.

This religious tone supports Augustan moral reforms without directly referencing law or authority. Poetry, rather than command, becomes the medium through which moral order is affirmed.

Poetry, Authority, and the Question of Propaganda

From a modern perspective, the poem raises difficult questions. Can a work commissioned by the state still be considered genuine literature? Does its close alignment with Roman political ideology diminish its artistic value?

These concerns are understandable, but they may reflect modern expectations more than ancient ones. In Imperial Rome, poetry and public life were not sharply separated. The social role of Roman poets included participation in communal meaning-making.

The Carmen Saeculare Within Horace’s Late Work

Horace appears to have accepted this role carefully rather than enthusiastically. The poem’s language suggests control rather than celebration. There is no sense of improvisation or emotional overflow. Instead, the work feels crafted to endure—not as an event, but as a memory of an event.

Within the wider Horatian work of ca. 18 B.C., the Carmen Saeculare represents the most openly public expression of Horace’s mature voice.

This poem becomes clearer when read alongside the wider discussion of the Horatian work of ca. 18 B.C., which explores how Horace’s mature poetry engages with Augustan culture and public life.

Why the Carmen Saeculare Still Matters

What ultimately gives the Carmen Saeculare its lasting importance is not its political usefulness, but its discipline. Horace understood the limits of poetry, and he worked within them. He trusted form, tradition, and shared belief.

Seen this way, the Carmen Saeculare is less a celebration of power than a reflection on continuity. It captures a moment when Rome wished to believe in its own stability, and it does so without exaggeration. That quiet confidence is the poem’s most human quality—and the reason it still matters.

More articles and ongoing work can be found on Hitaar, where different topics are published and updated regularly.