The Horatian work of ca. 18 B.C. belongs to a moment in Roman history when literature was being asked to do something unusual: to help a society believe in itself again. Rome had survived civil war, political betrayal, and decades of instability. By the late first century B.C., exhaustion was widespread, not only among citizens but within Roman culture itself. The rise of Augustus promised stability, yet stability alone was not enough. It had to be explained, justified, and emotionally accepted.

This is where poetry entered the picture.

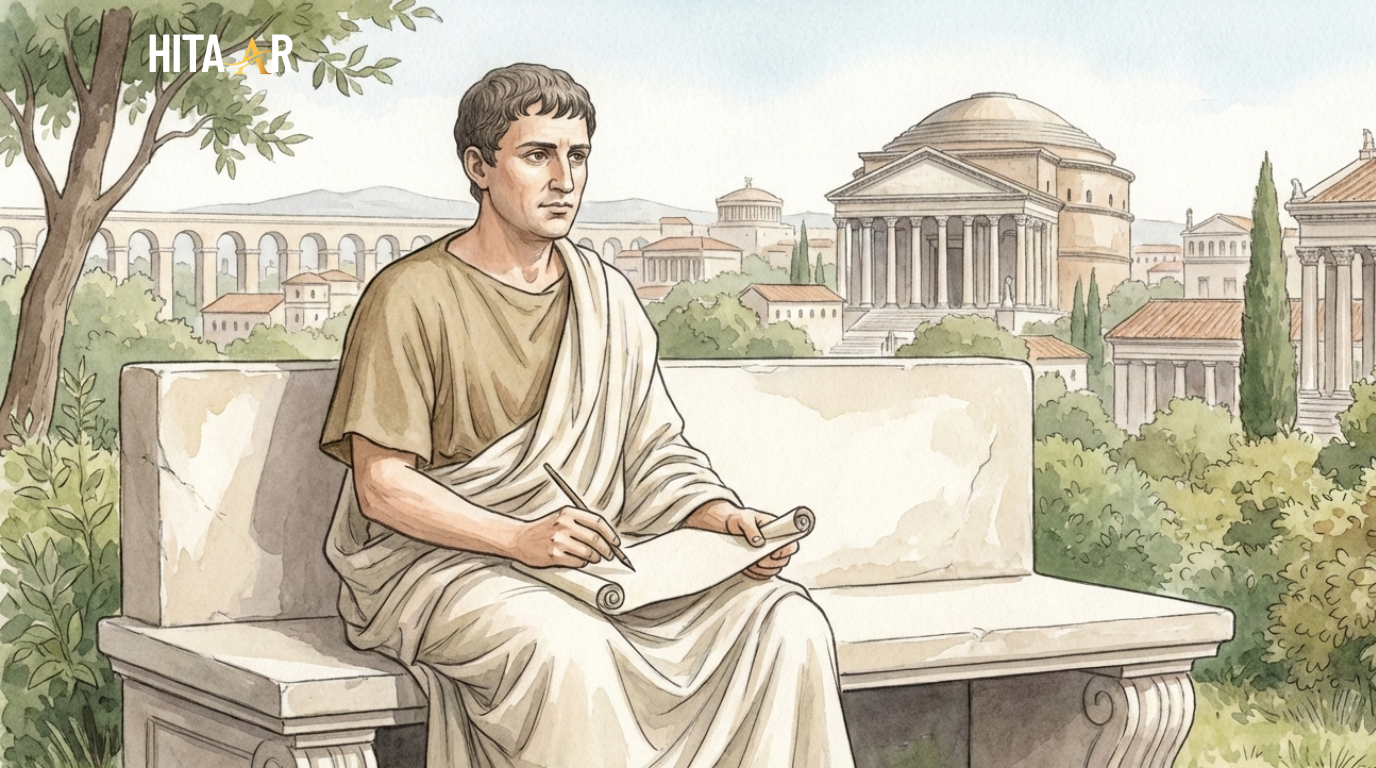

Horace was not an official spokesman, nor was he a detached observer. He occupied a space between private reflection and public responsibility. His work around 18 B.C. reflects a poet who understood that words, when carefully chosen, could shape how people felt about the present and imagined the future. Within Classical Roman literature, this period of Horace’s writing shows a remarkable shift—from irony and distance toward calm authority.

What matters most here is not what Horace says, but how quietly he says it. It speaks to readers quietly. And that quietness, in the context of Augustan Rome, was itself meaningful.

Historical Background of Horace and Augustan Rome

To read the Horatian work of ca. 18 B.C. properly, one must begin with Horace himself. He was not born into power or privilege. His early life unfolded against the collapse of the Roman Republic, a time marked by violence, confiscation of land, and political fear. Horace even fought on the losing side at Philippi, an experience that left him personally and financially exposed.

Those experiences stayed with him, and they show in how cautiously he writes later. He did not romanticize politics. He understood its cost.

When Augustus emerged as Rome’s sole ruler, Horace was already middle-aged, already cautious. The peace that followed was not abstract to him; it was felt. There is a noticeable easing in the later poems — relief, perhaps, but never celebration. The Rome of the Augustan Age was calmer, more controlled, but also deeply aware of what had been lost.

In this historical context, Horace’s poetry becomes a record of adjustment. It shows how an individual’s mind adapted to a new political reality, one that valued order over debate and continuity over change. One of the clearest examples of Horace’s public role as a poet appears in the Carmen Saeculare, a work written for a specific civic occasion and explored in detail in our focused discussion of its purpose and historical importance.

Political and Cultural Climate of ca. 18 B.C.

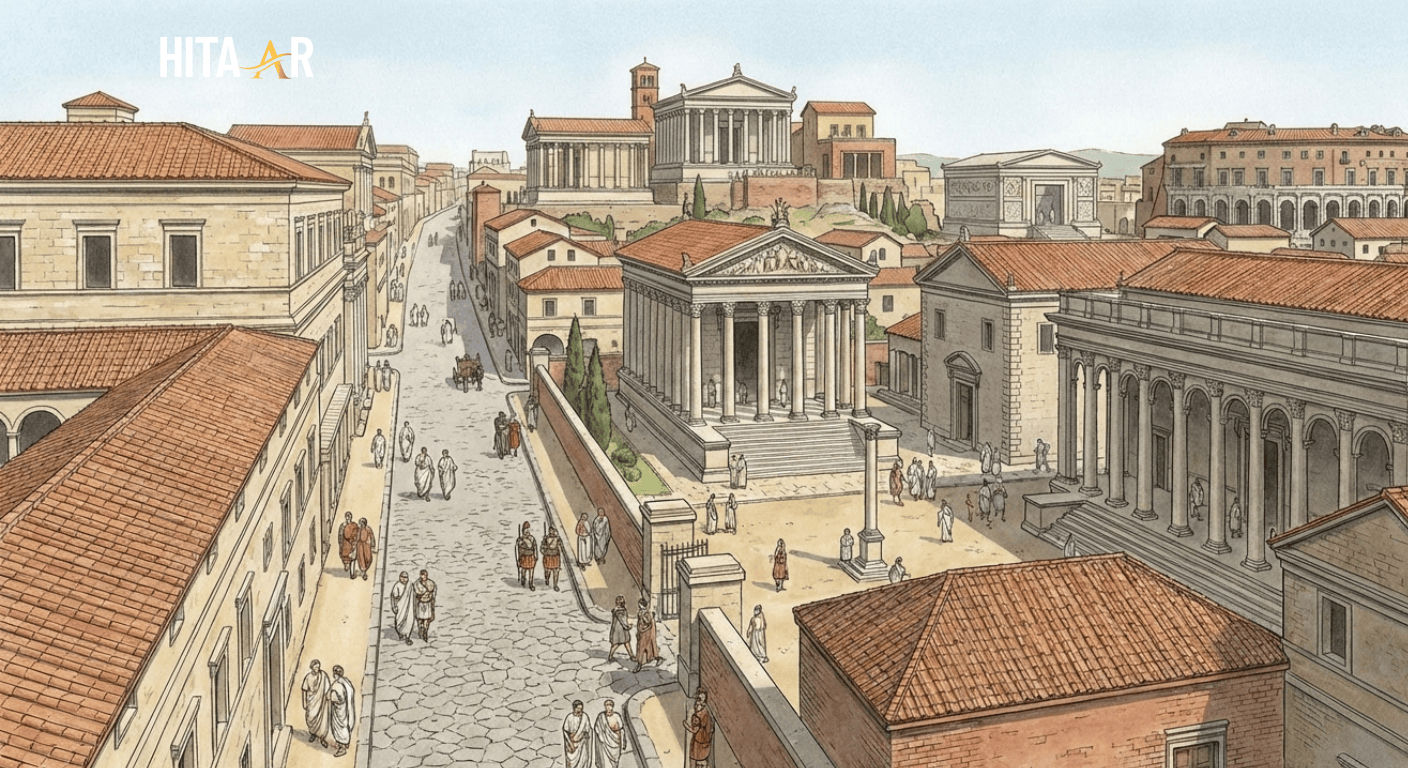

By 18 B.C., Augustus had moved beyond securing power. His focus had shifted toward shaping Roman society itself. Laws concerning marriage, family life, and religious observance aimed to restore traditional values. These Augustan moral reforms were not simply political measures; they were cultural statements.

Rome, at this point, was attempting to define what it meant to be Roman again.

Literature mattered here precisely because it worked quietly, without commanding attention. Unlike speeches or laws, poetry worked indirectly. It did not instruct citizens what to think; it shaped the emotional atmosphere in which thought occurred. Horace’s writing from this period seems shaped by that expectation.

The poetry does not celebrate conquest. It does not glorify violence. Instead, it emphasizes moderation, balance, and respect for tradition. These qualities aligned closely with Roman political ideology, yet they were expressed in a way that felt personal rather than imposed.

This is why Horace’s work was trusted. It did not feel like a policy written in verse. It felt like a reflection shaped into form.

Patronage of Maecenas and Literary Authority

The patronage of Maecenas is central to understanding Horace’s authority as a poet. Maecenas was not merely a wealthy supporter; he was deeply involved in the cultural direction of Augustus’ Rome. His circle included poets who would come to define Augustan literature.

Yet patronage did not erase individuality. Horace’s poetry does not sound like an obligation. Instead, it reflects mutual understanding. He was given security, and in return, he contributed to Rome’s cultural project—not blindly, but thoughtfully.

The relationship is more complicated than simple dependence, and Horace appears to have known that. Poets were not free in a modern sense, but neither were they powerless. Horace’s strength lay in knowing where expression ended and responsibility began.

Through this balance, he achieved lasting literary authority, respected both in his own time and long after.

The Horatian Work and Augustan Ideology

Modern readers often approach this work with suspicion, asking whether it simply supports power. This question misses something essential. Horace’s poetry does not argue ideology; it normalizes it.

Rather than promoting Augustus directly, Horace presents a world where stability, peace, and reverence already feel natural. In practice, this kind of indirect influence often worked better than open argument. The poetry does not persuade—it assumes.

Within discussions of Augustan ideology in literature, Horace’s work stands as a model of indirect influence. It shows how poetry can reinforce political values without sacrificing artistic subtlety.

This approach explains why the work still rewards close reading. It is layered, not loud.

Modern understanding of Horace’s role in Augustan culture is shaped in part by long-standing academic scholarship produced within university classics departments.

Themes, Style, and Roman Values

The thematic structure of the Horatian work of ca. 18 B.C. reflects restraint. Time appears as a quiet presence, reminding readers of human limitation. Pleasure exists, but always within measure. Duty is present, but not heavy-handed.

The famous carpe diem theme survives here in a softened form. It no longer urges immediate enjoyment but thoughtful appreciation. This shift reflects Horace’s own maturity and the moral climate of Augustan Rome.

Stylistically, Horace’s control of Roman lyric poetry is complete. His use of meter, balance, and tone reflects discipline. The Greek influence on Horace is visible, but always adapted. Greek intensity becomes Roman order.

The poems feel built piece by piece, with emotion held firmly in check. That calmness is deliberate.

Literary Significance and Cultural Impact

The significance of Horatian poetry lies in its endurance. It shaped expectations for lyric writing long after Augustus was gone. Later poets admired Horace not because he flattered power, but because he demonstrated how poetry could exist within power without dissolving into it.

Within Classical Roman literature, his work helped define the role of the poet as a cultural stabilizer. Not a rebel. Not a servant. Something in between.

Long after Augustus, readers continued to return to Horace for his restraint rather than his politics.

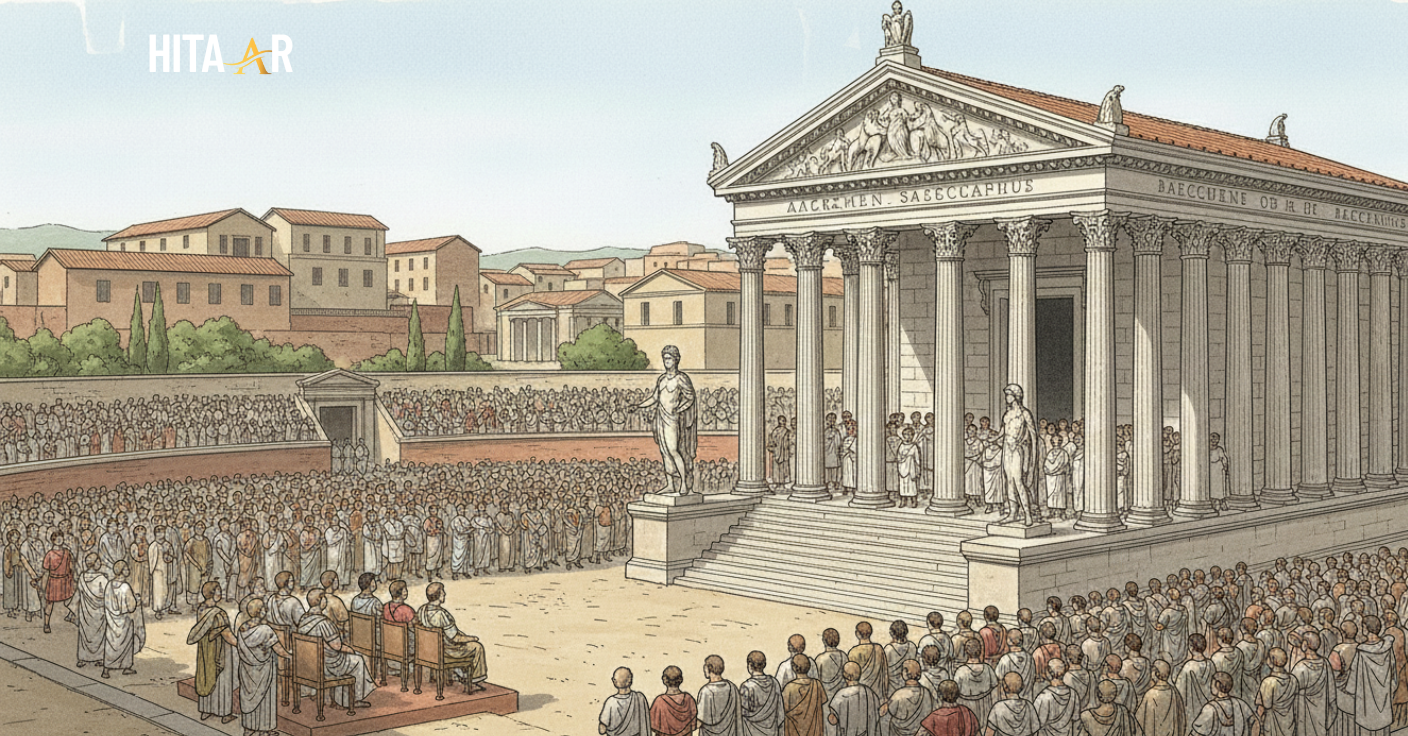

Carmen Saeculare and the Secular Games

The clearest example of Horace’s public role is the Carmen Saeculare, written for the Secular Games of 17 B.C. This poem was performed, not read. It belonged to ritual and memory.

As public ceremonial poetry, it marked renewal. The poem did not debate Rome’s future—it affirmed it. Sung as a Latin choral song, it created a shared emotional experience that connected religion, history, and identity.

Public Ceremonial Poetry in Imperial Rome

In Imperial Rome, poetry often moved beyond private spaces. Ceremonial works reinforced collective values and shared beliefs. Horace succeeded here because he respected tradition and avoided exaggeration.

His poetry fit the moment without overwhelming it.

Horace’s Lyric Technique and Greek Influence

Horace’s lyric technique reveals deep respect for Greek forms, but also confidence in Roman adaptation. He refined, shortened, and disciplined what he borrowed. The result feels Roman in temperament—controlled, reflective, grounded.

This technique helped solidify the Roman lyric tradition.

Moral Philosophy and Civic Responsibility

At its core, the Horatian work of ca. 18 B.C. presents a quiet moral philosophy. Life is finite. Excess is dangerous. Community matters. Civic responsibility is not enforced through fear, but encouraged through example.

This philosophy explains why the work still feels human. It does not demand belief. It invites balance.

This article was written by a student and researcher of Classical Roman literature, with a focus on Augustan poetry and Roman cultural history. The analysis is based on close reading of primary texts and modern literary scholarship.

For more carefully researched articles on literature, history, and culture, visit Hitaar, where we publish in-depth guides designed for students and readers alike.